Table of Contents

Content Warnings: death, murder, violence, blood, vampirism, suicide, loneliness and social isolation, aging and elderly characters, queer longing and unfulfilled desire, grief, period-typical homophobia (1980s flashbacks), emotional manipulation

At its core, this is a book about the kind of loneliness that persists even in a life filled with relationships. I read it on honeymoon—almost a year late because of cancer treatments—and understood immediately what Cheon Seon-Ran's vampires were hunting. Cancer ghosting taught me: you can be most alone with a contact list full of outgoing messages that have spent months on read, as if 'Stage IV' leaves you socially dead before you're physically gone.

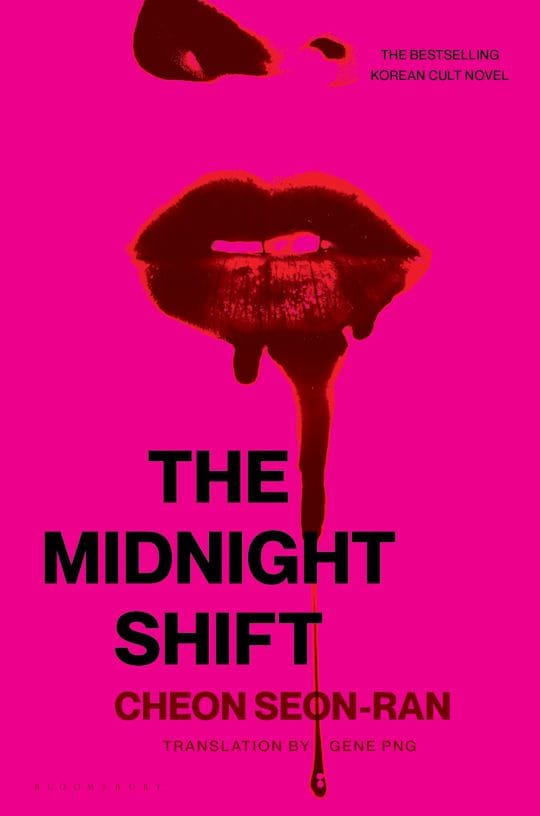

That's the blood Cheon's vampires track in The Midnight Shift (originally 밤에 찾아오는 구원자, "the saviour who comes in the night"), sutured into English by Gene Png—not physical isolation but structural erasure. On that examination table, what could be mere Gothic decoration becomes a surgical social analysis, and Png's translation hands us the scalpel.

Three POVs make incisions through different timelines—the hunter, detective, and immortal predator—with a memorandum of understanding that feels bureaucratic, but which ultimately reveals real forms of power. These vampires can't be killed unless they're feeding on the unwilling, so consent becomes the incision point through which this social surgery is performed. Cheon structures that predation as a societal failure rather than a supernatural threat. No, her vampires don't stalk the physically alone, as is so often the case. Instead, they track the socially exiled: the elderly whose families stopped calling them, or those in the queer community whose longing "due to social judgement" (the author's translated phrasing) becomes its own kind of dying. The 1980s France flashbacks—and a formative relationship therein—don't sentimentalise this; they show how intimacy and isolation wind together, and thus how queer romance can be both a refuge and its own peculiar abandonment. These three narrative threads do occasionally tangle rather than weave neatly—one chapter lost me for a bit until I backtracked and sorted out which timeline we were following.

Png's translation rarely catches on anything, often making me forget I'm outside Korean literary traditions, except in rare moments when Png's steady hand falters and something bleeds through untranslated—a Korean literary nerve I can name but not touch. It's like overhearing snippets of conversation in a dialect I don't speak, but a language I do. I don't know how the book reads in its original context—what resonances it carries in Korean horror traditions or in what ways Korean readers catch the scent of queerness differently than I can. What I can see, though? How murder mystery mechanics create a pressure that forces characters to articulate a loneliness they'd rather leave unnamed. How the three narrative strands stay tangled up in each other without any hierarchy of their importance. Each POV character's loneliness has a different blood type, and Cheon refuses to make any of them a universal donor.

The author describes writing queer characters as being "simply familiar," and connecting the loneliness of aging to the queer experience of loving "but not being able to be with them." The book bleeds that connection through every page. The elderly patients whom the vampires target aren't just old and ailing but socially exiled; queer desire isn't just forbidden but literally consumes. Whether this connection reads differently in a Korean cultural context than it does filtered through Png's English, I'm unsure. I do recognise the ache of being looked through rather than at and the exhaustion of performing normalcy while feeling like I'm bleeding out. The book's murder mystery sometimes feels like the bait that leads us to this snare of recognition rather than plot with its own momentum—which might frustrate readers who expect procedural satisfaction—but that reads like design, not accident.

Who will find this good literary medicine? Readers hungering for fiction that bleeds across genre lines—queer Gothic meets Korean murder mystery meets sociological diagnosis. Those who appreciated Our Wives Under the Sea giving loneliness its own grit, making it something that sticks to your palm like wet sand, or anyone who wants more vampire fiction doing social analysis. Leave it on the shelf if you need romances perfectly sutured or mysteries with no lingering side effects. Cheon leaves some knots untied, and there's at least one subplot where I'm still not sure if it was forgotten or purposefully left adrift.

I closed the book still uncertain about all that I'm outside of. Korean literary traditions? Queer Korean contexts? Translation gaps where meaning loses the scent in crossing? That uncertainty only enhances the point. Loneliness is often about witnessing what you can't quite reach, tracking the scent of something just beyond translation.

Comments